So long, farewell… the number of people leaving B.C. hit a new record

In the musical, The Sound of Music, the von Trapp children sing the chorus of the famous song, “So long, farewell,” before a ballroom filled with their father’s assembled guests. One of the children, seven-year-old Marta, then steps forward to sing the next line, “I hate to go and leave this pretty sight.” Perhaps this sentiment was on the minds of the nearly 70,000 residents who left beautiful British Columbia for other parts of Canada over the past year.

Net interprovincial migration to B.C. is typically positive…

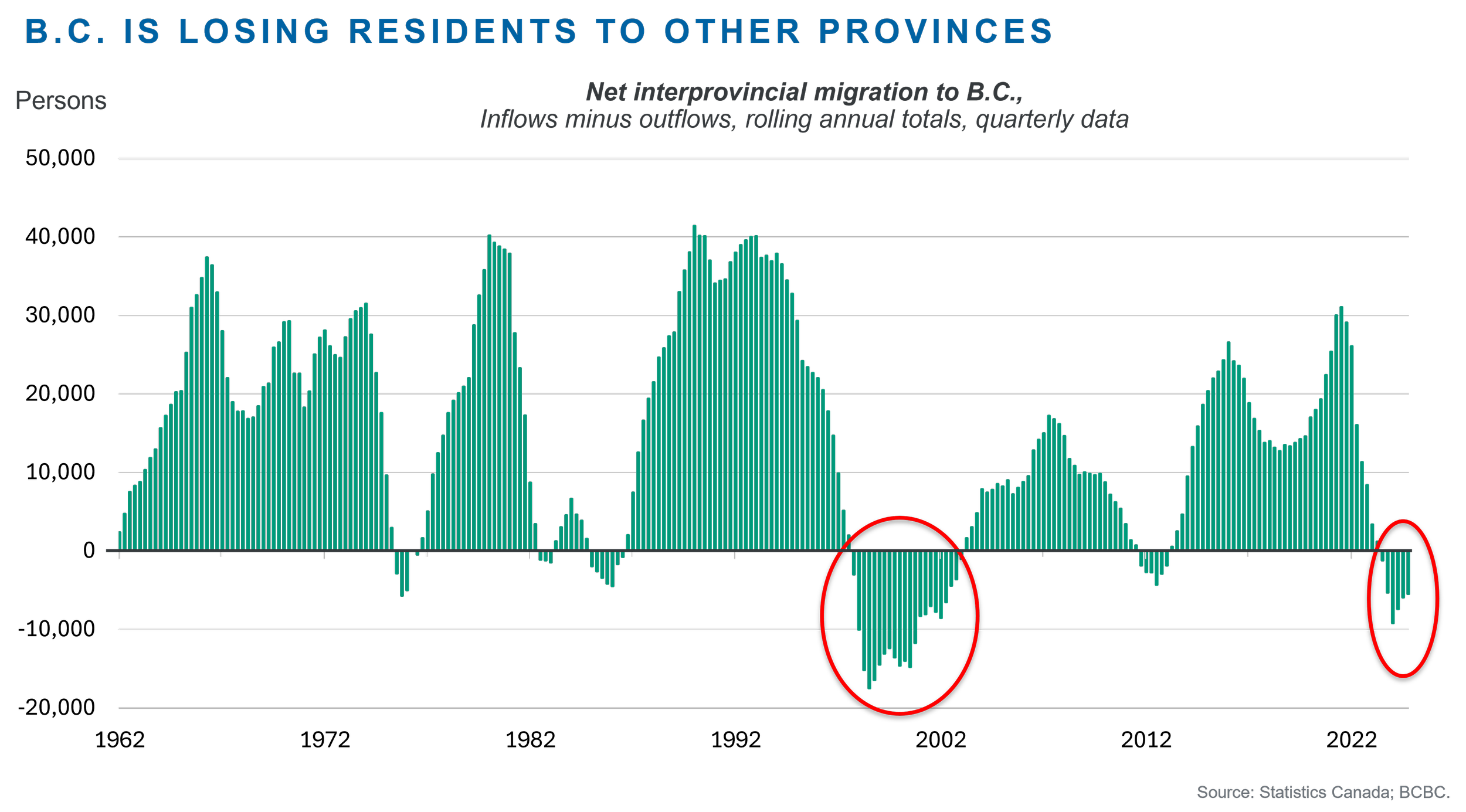

Since 1962, net interprovincial migration (i.e., inflows minus outflows) to B.C. has typically been positive and averaged around +14,000 per annum. This means, on average, around 14,000 more people came to live in B.C. from other provinces than left B.C. to live in other provinces over the year.[1] Net interprovincial migration to B.C. in some periods – such as during roughly 1965-74, 1978-81, 1988-96, 2015-16 and 2021-22 – has been as high as +20,000 to +42,000. Positive net interprovincial migration can indicate relatively attractive economic opportunities and better social services compared to other provinces.

…But recently it has turned sharply negative

Since around 2023, B.C. has seen net interprovincial migration turn sharply negative by around -5,000 to -9,000 per annum (Figure 1). This is unusual. The province has not seen negative net interprovincial migration of this magnitude since the 1998-2002 period. Other than during 1998-2002, periods of net interprovincial migration have tended to be short lived and small in magnitude. Moreover, they tend to coincide with periods of weak provincial economic activity compared to the rest of Canada.

Figure 1

Why is net interprovincial migration negative?

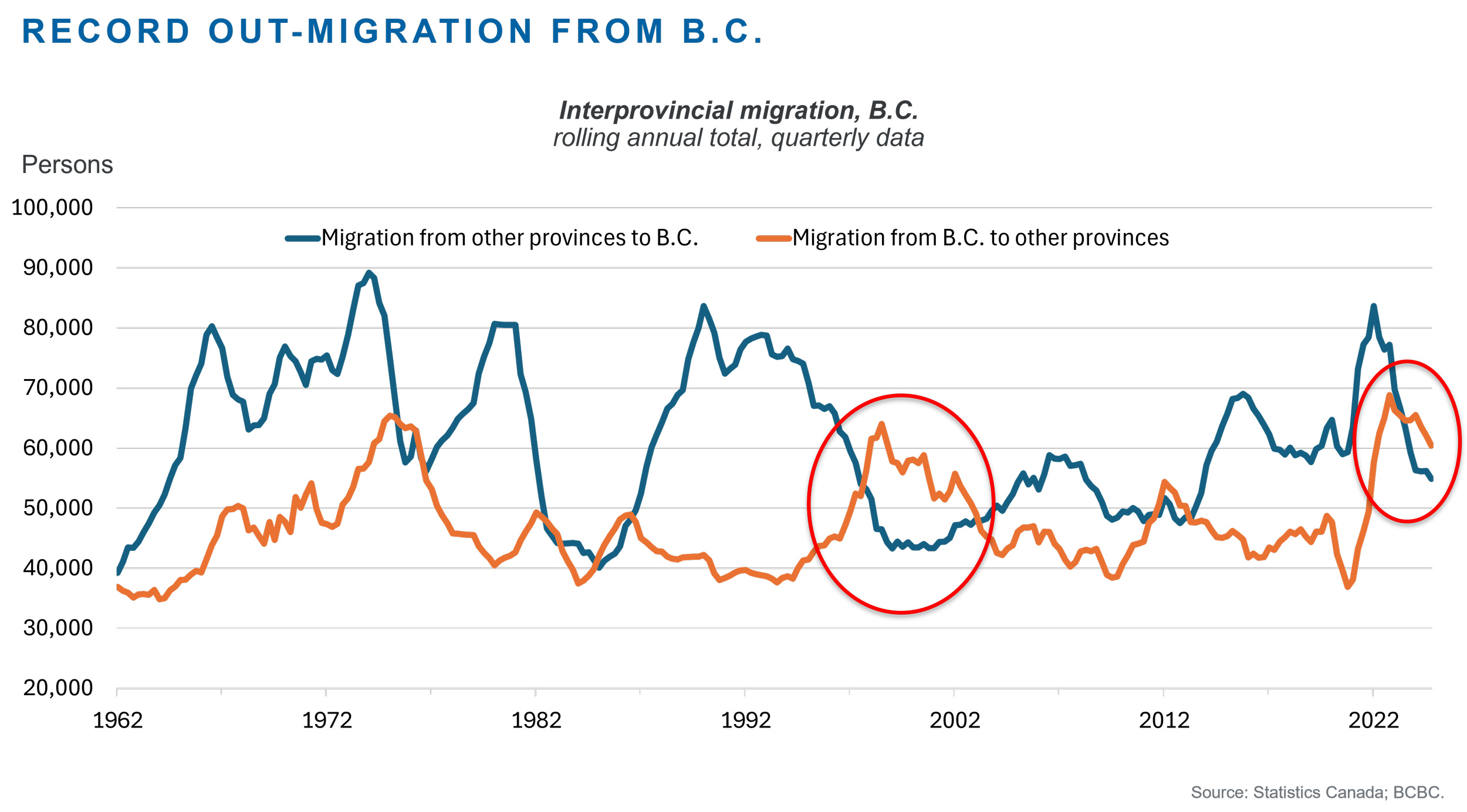

Is negative net interprovincial migration the result of high outflows of B.C. residents, low inflows of residents from other provinces, or both? Figure 2 provides a breakdown. Out-migration of B.C. residents to other provinces has surged to nearly 70,000, a record level. By comparison, the next closest peaks in out-migration were 64,000 in 1998 and 65,000 in 1975. Meanwhile, in-migration to B.C. from the rest of Canada has dropped to around 55,000, which is modestly below its long-term average of around 62,000. Thus, B.C.’s negative net interprovincial migration is mostly due to a surge in out-migration and, to a lesser extent, weak in-migration.

Figure 2

Where are British Columbians going when they leave?

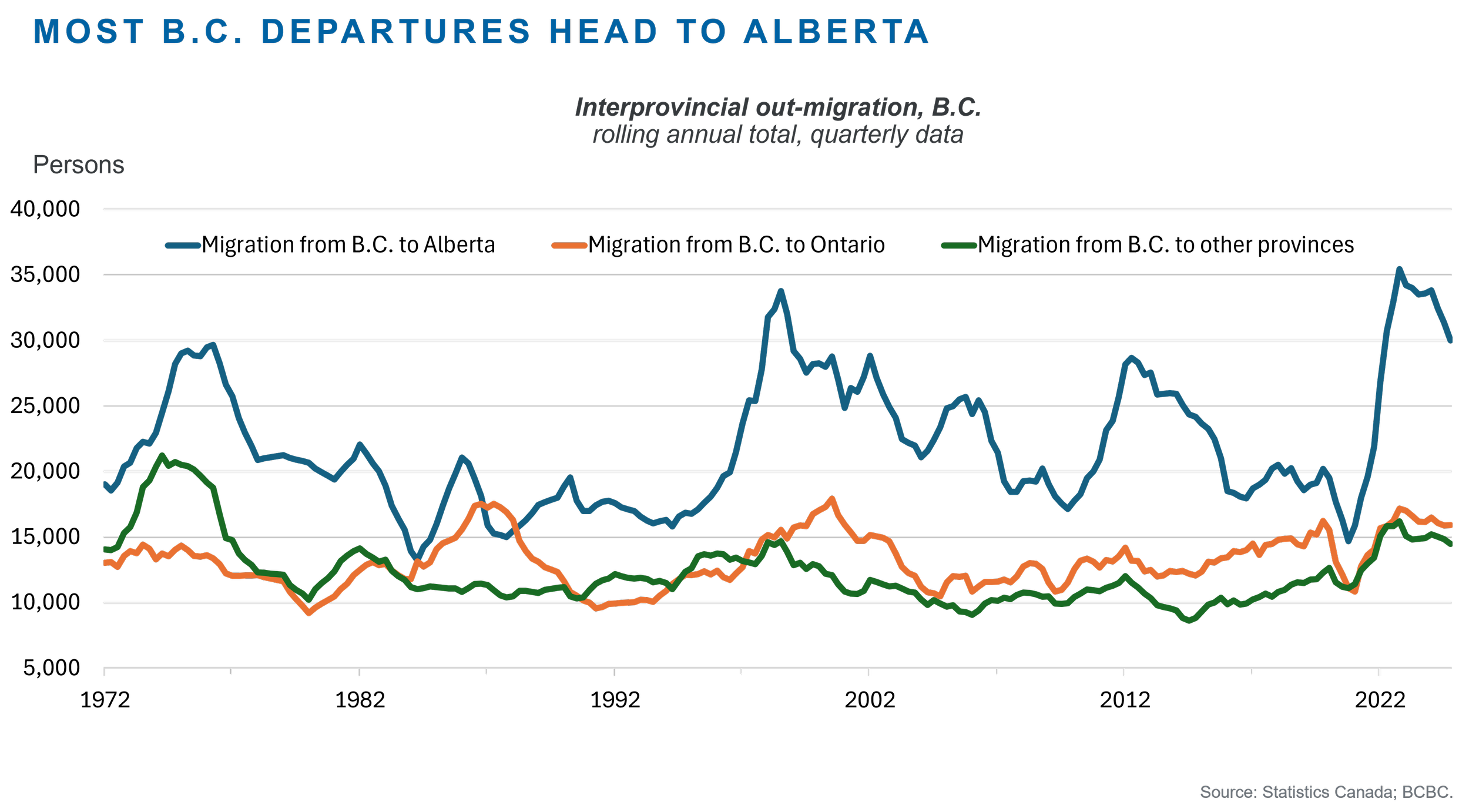

Figure 3 shows where British Columbians have moved when they leave the province. It tracks interprovincial out-migration from B.C. to Alberta, Ontario, and all other provinces since 1972. Since 1972, nearly 8 in 10 residents leaving B.C. have moved to just two provinces: Alberta and Ontario. Alberta alone has drawn about half of all out-interprovincial migrants, likely reflecting its higher average incomes, lower taxes and cost of living, and close geographical proximity.

From 1972 to 2019, an average of about 21,500 people moved from B.C. to Alberta over the course of a year. But since the third quarter of 2022, every quarter has seen the number of people moving to Alberta over the previous 12 months rise above 30,000, which is well above the long-term average. Out-migration to Alberta reached a record high in the first quarter of 2023, with more than 35,000 British Columbians making the move over the previous year.

Figure 3

Who is the typical interprovincial migrant?

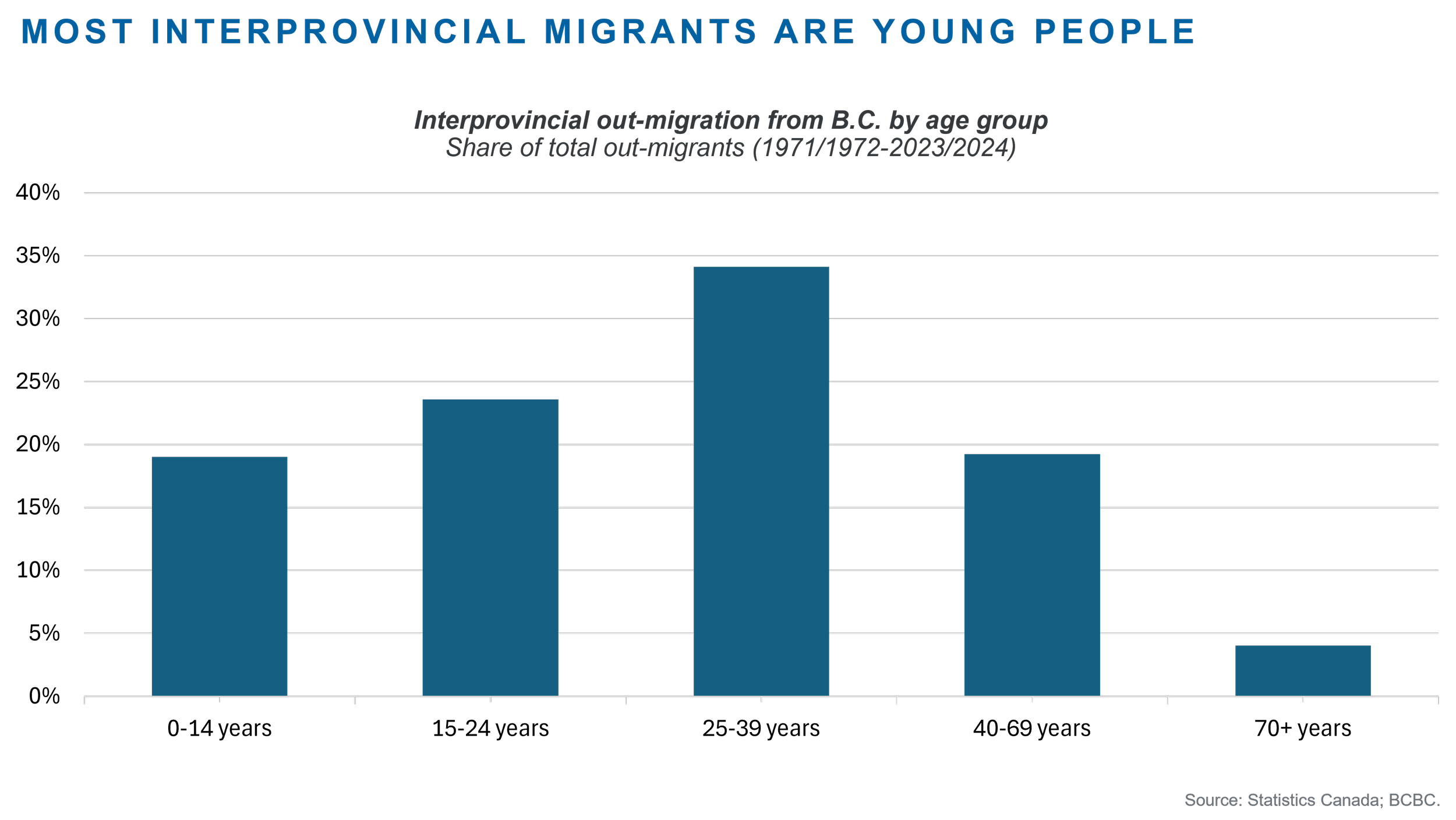

Interprovincial migrants tend to be young, highly educated, and economically motivated. B.C. data shows that younger people, particularly those aged 25-39 years and 15-24 years, consistently account for the largest shares of interprovincial out-migrants (Figure 4). In fact, 77% of all B.C. interprovincial out-migrants since 1971 have been under the age of 40.

According to Coulombe and Tremblay (2009), interprovincial migrants are also more skilled and better educated than the residents who remain, contributing to a redistribution of human capital across provinces. Serlenga and Shin (2020) find that higher income levels and lower unemployment rates in destination provinces increase inflows, while the opposite in origin provinces encourages outflows. Thus, income and employment opportunities are important drivers of interprovincial migration. Taken together, the evidence suggests that interprovincial migrants tend to be younger adults with higher levels of skills and education who are responsive to economic conditions.

Figure 4

Conclusion

B.C. has historically attracted more residents from rest of Canada that it lost to other provinces. That’s no longer the case. Net interprovincial migration has turned negative in a way not seen since the 1998-2002 period. Young, skilled, and aspirational people follow economic opportunities: they vote with their feet. Increases in out-migration tend to coincide with periods of sluggish economic activity. Our previous blogs discuss B.C.’s recent economic performance across industries (Williams, 2025) and in the labour market (Yunis, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c).

People leaving B.C. tend to be young, aged 25-39 years and 15-24 years, and skilled. This makes it challenging to build successful businesses because companies rely on being able to hire from a deep pool of up-and-coming skilled workers. Moreover, these age groups are likely to be net contributors to the tax base (i.e., pay more in taxes than they consume in public services). Thus, negative net interprovincial migration is likely to be a drag on the provincial budget. Residents who remain in B.C. are likely to face some combination of higher future tax burdens, higher public borrowing, or constrained growth in spending on public services like hospitals and schools.

British Columbians should be concerned about large, sustained, negative net interprovincial migration. It is an important barometer on the health of B.C.’s economy, a “canary in the coalmine.” The most pressing challenge facing policymakers is how to restore vibrancy to B.C.’s private sector. BCBC’s provincial policy recommendations on how to do so are here. The top three are briefly outlined in Williams (2025).

We hope the province will not be like the audience of assembled guests in The Sound of Music and simply respond to those departing, “Goodbye.”

[1] Note that net interprovincial migration excludes international migration (i.e., people arriving to B.C. from other countries or leaving B.C. for other countries).